By Leslie Fishbein

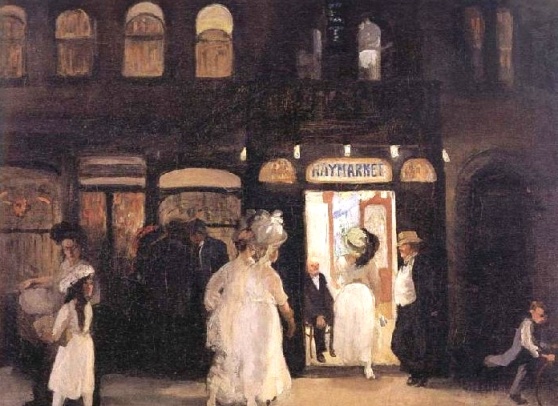

I started writing about prostitution because I found American attitudes toward it paradoxical. The radical writers and artists who contributed their work to The Masses, a socialist literary and political magazine published in Greenwich Village from 1911-1917, and also the subjects of my first book, Rebels in Bohemia, should have condemned prostitution as a product of capitalist greed but instead they glamorized it and celebrated prostitutes as emblems of sexual freedom, as in this 1907 John Sloan painting of elegantly attired prostitutes entering the Haymarket Saloon.

As I explored popular representations of prostitutes, I began to wonder about what prostitutes and madams thought about these representations and how they conceptualized their own situation. As a result, I began reading their memoirs and interviews and viewing documentary films and docudramas focusing on them. As a result, I learned about the notorious Manhattan madam Polly Adler, whose clients included gangsters Charles “Lucky” Luciano and Dutch Schultz, boxer Jack Dempsey, New York City Mayor Jimmy Walker, and members of the Algonquin Round Table, a coterie of writers and journalists that included Dorothy Parker and Robert Benchley.

Polly Adler shields her face as she exits court. Courtesy of the New York Daily News.

I also began to investigate prostitutes’ rights organizations beginning with C.O.Y.O.T.E. (Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics), founded by Margo St. James in San Francisco on Mother’s Day in 1973.

Again there were many paradoxes. C.O.Y.O.T.E. included many non-prostitutes among its membership. In fact, according to the C.O.Y.O.T.E. records on file at the Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe, “in 1975 only 60 of COYOTE’s 8500 members admitted to being prostitutes; most members were educated, white, middle-class women.” Clearly the prostitutes’ rights movement spoke to sexual and gender concerns of non-prostitute women, possibly even more compellingly than it spoke to prostitutes themselves. Also, while C.O.Y.O.T.E. engaged in serious and substantial educational campaigns, including AIDS education and debunking the myth that prostitutes were primarily responsible for the spread of venereal disease, the organization used the kind of humor to advance its cause that would be likely to offend potential donors and supporters (as can be seen by the propaganda buttons above).

While sociologists may classify prostitutes as social deviants, my research indicates that often they have influenced mainstream culture.

A case in point is the widespread popularity of the 1961 Hollywood film version of Truman Capote’s 1959 novella Breakfast at Tiffany’s. While Holly Golightly clearly is a lady of the evening who sustains her bohemian life style by accepting men’s fifty dollar tips for the ladies’ room, Holly has been transformed into an icon of style – what fashionable woman is without a variant of the Givenchy “little black dress” that Hepburn helped to popularize via the film? – and her image has been transformed into paper dolls with which little girls play despite the morally dubious source of support for her fashion.

What I have learned from my research is that initial appearances can be deceiving and that culture and society are often shaped by irrational forces of which social actors are not always fully conscious.

While we tend to be aware of the ways in which prostitutes have been exploited sexually, we fail to realize the degree to which they also have been exploited as a means of addressing social and cultural tensions that we fail to confront directly.